Late in 2013, a series of lawsuits that had ricocheted around courts in the U.K. Wilson-didn’t have all the materials to fully return Bond to his Beatles Invasion-era primacy until two years ago, after Skyfall had become the highest-grossing film of all time in Britain. That this new M is played by Ralph Fiennes is small compensation for Dench’s departure after a seven-picture tour of duty, but still a promising development.Įven so, the keepers of the Bond flame-Barbara Broccoli, the daughter of the original series producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, and her half-brother, Michael G. Once again, Bond is receiving equipment and derision from Q, flirting with Miss Moneypenny, and-for the first time since 1989’s grim Licence to Kill-taking orders from a man. Still, M covers for him, and by the end of Skyfall’s deflating, rather too Home Alone-inspired final act, nearly all the familiar characters and tropes that Casino Royale had stripped away have regenerated.

When he finally reports for duty (by breaking into M’s flat, a fun callback to Casino Royale), he’s out-of-sorts, out-of-shape, and addicted not just to booze, but pills. Early on in the movie, MI6 believes that Bond’s been killed by friendly fire, and he’s in no rush to let the agency know he’s survived. Skyfall, Craig’s third outing in the role, is set much later in Bond’s career than his first pair of appearances. If Casino Royale was recognizably an adaptation of an Ian Fleming novel, Spectre is more like an attempt to film the Bond franchise’s Wikipedia page. The organization has its tentacles in phony pharmaceuticals and human trafficking, it’s revealed, but it doesn’t declare allegiance to abstraction, because under the regime of the director Sam Mendes and the writer John Logan (both returning from Skyfall), the Bond film franchise is now more than ever an abstraction unto itself. SPECTRE is no longer an acronym, or if it is, no one troubles themselves to spell it out. Meanwhile, the series’s brief detour into something approximating realism is concluded.

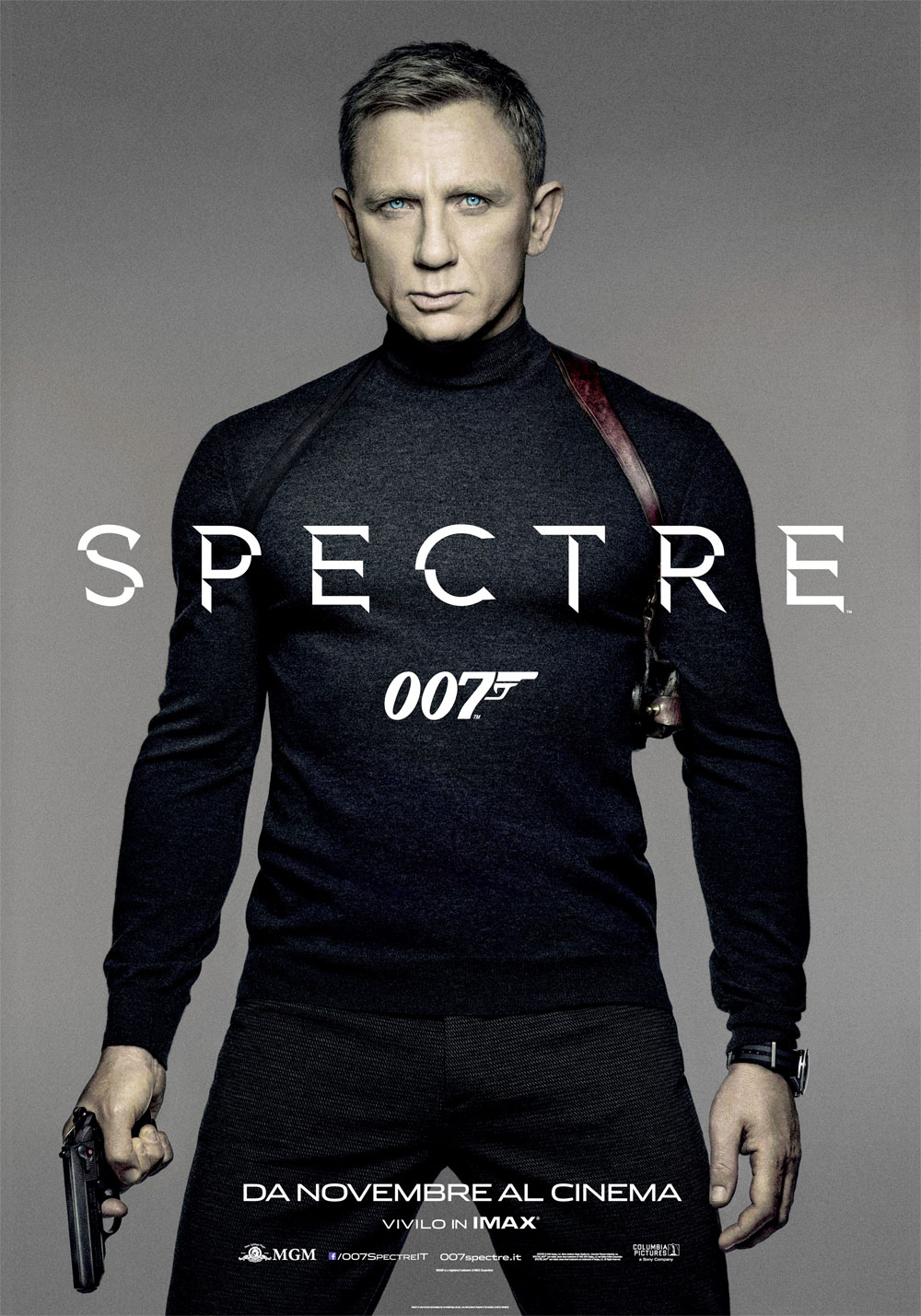

In Spectre, Craig seems more Connery-like-fearless, entitled, and inscrutable-than ever. But the 38-year-old actor’s command of the role turned out to eclipse even Sean Connery’s. Daniel Craig’s leaner, greener, deadlier 007 was a “blunt instrument,” in the withering description of his boss, Judi Dench’s M. In their place was the closest that action-adventure cinema ever gets to a character study. Six years earlier, Casino Royale had given the (re)boot to decades of accumulated shark tanks and volcano lairs and disposable women with names like Pussy Galore and Holly Goodhead and Plenty O’Toole. The last scene of 2012’s Skyfall, the most lucrative and critically admired entry in the always profitable, suddenly venerable franchise, teased a restoration. That the 24th “official” James Bond film is called Spectre feels like a promise kept. While the legal battle over which creator had dreamt up what would outlive them all, one thing was clear: No one could think of a suitably menacing word that began with the letter “P.” Decoded, the name stood for SPecial Executive for Counterintelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion. Their future-proof solution was SPECTRE, an organization that used Space Age, acronym-generating technology to ally itself not with any political or economic system, but to assorted malign abstractions. Nothing Says Midwest Like a Well-Dressed Porch Goose Julie Beck

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)